GROSSVENEDIGER, 3660 m

(T.) Wenn das Kleid der Erde in hundertfältiger Blütenpracht sich wieder erneuert, und jugendlich grünende Gefilde den herannahenden Frühling künden, wenn die Sonne den frostglitzernden Panzer, mit dem die nordischen Wintergötter die Berge umfangen haben, wegzunehmen droht, dann drängt es uns noch einmal hinaus, Abschied zu nehmen von der unendlichen Stille winterlicher Hochwelt, von der hehren Pracht sonnig glänzender Schneedome. Noch einmal wollen wir in der Zeit, die so viele Jahre lang die Berge als verschlossenes, unnahbares Gebiet erscheinen ließ, in die schimmernde Hochregion Vordringen, wollen in atemraubender Gleitfahrt zu Tal jagen, noch einmal in kühnen Schwüngen die Steilheit meistern, um dann unsere treuen Begleiter in den sommerlichen Ruhestand zu versetzen und wieder Pickel und Seil hervorzusuchen. Ostern! Das ist für den alpinen Schneeschuhläufer so recht die Zeit zu Gletscherfahrten. Die Tage sind schon lang, Schönwetter oft meist anhaltend die Eisströme von metertiefem Schnee bedeckt, die Spalten gut überbrückt: da läßt sich die Sehnsucht nach einem größeren Unternehmen nicht mehr unterdrücken. Diesem Drange folgend, fuhr ich in Gesellschaft Gleichgesinnter im „Zügle" der Krimmler Bahn durch das Salzachtal. Der Hauptort des Pinzgaus, Mittersill, war bereits durchfahren, wir näherten uns der Mündung des Untersulzbachtales, wo sich ein prächtiger Blick auf den unumschränkten Herrscher des ganzen Gebietes, auf „unseren" Gipfel, bot und bald nachher hatten wir auch die Haltestelle Rosental-Großvenediger erreicht. 1/2 10 Uhr vormittags war es — eine mehr als zwölfstündige nächtliche Bahnfahrt hatte uns von Wien hierher gebracht —, nun hieß es tüchtig ausschreiten, um die bedeutende Höhe der Kürsingerhütte, 2558 /n, noch vor Einbruch der Dunkelheit zu bezwingen.

Über den schneelosen Talboden wanderten wir, die Bretter auf den Schultern, der Öffnung des Obersulzbachtals zu und folgten dem Alpenvereinsweg zur Hütte. Nach kaum mehr als halbstündigem Aufstieg lag bereits genügend Schnee, um anzuschnallen. Immer weiter ging's talein über die Reste zahlreicher Lawinen, die vielleicht vor wenigen Tagen in das tiefeingeschnittene Tal herabgeschossen, zur Steilstufe des Seebachfalls. Wir durchfuhren sie in tief verschneitem Wald, den langen Kehren des Reitweges entlang, und erreichten die Berndlalpe, wo wir uns ein sonniges Plätzchen zur Mittagsrast wählten. Diese Talstufe bietet den ersten Blick auf das Obersulzbachkees. Mit scharfen Konturen vom Blau des Himmels abgegrenzt, schien es wie ein mächtiger Strom die verschneiten Felsen des Geigers zu umbranden. In flimmernder Märchenpracht und unentwegter Stille lag die Gletscherwelt vor uns — ein glanzvolles Bild des unwandelbaren Waltens starrer Naturgesetze, so recht ein Ort, die Verehrung zu verstehen, die unsere Zeit dem Schönen und Erhabenen im Hochgebirge entgegenbringt! —

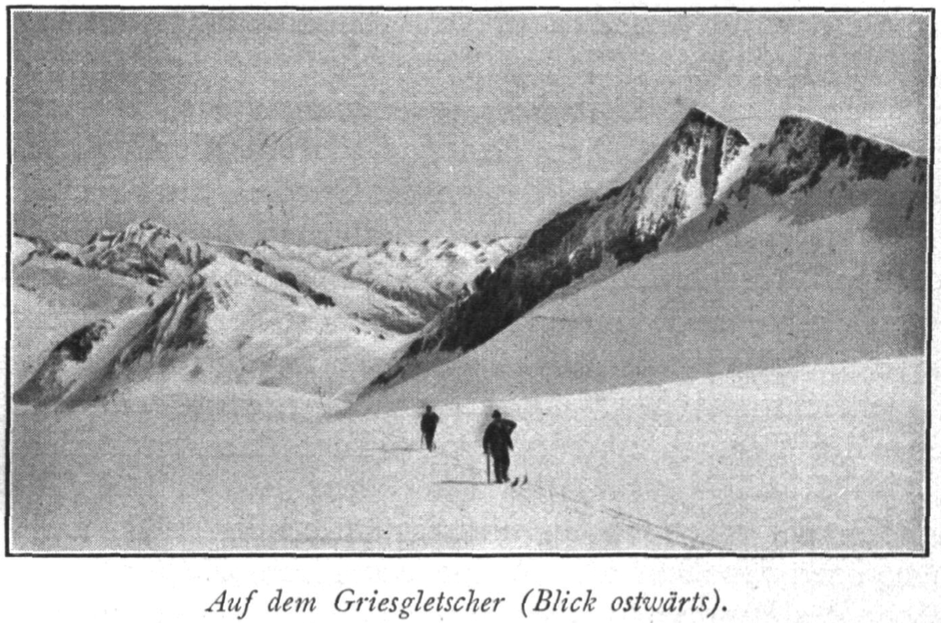

Nachdem wir den Mundvorräten unserer Rucksäcke tüchtig zugesprochen hatten, fuhren wir wieder weiter an der Aschamalpe vorbei, über wellige Almböden zum Gletscher empor. Mit jedem Meter Höhe, den wir gewannen, wurde die Umgebung großartiger. Die Eiskatarakte der „Türkischen Zeltstadt", die den Absturz des ausgedehnten Keeses gegen seine Zunge hin bilden, prägten sich unauslöschlich in mein Gedächtnis ein. In einer Kaskade von wild übereinander aufgetürmten Eisblöcken liegt das verworrene Kluftsystem neben uns. Abgrundtiefe, bläuliche Schlünde neben tausendfach schimmerndem Schnee, seltsam geformte Eisgebilde neben zerborstenen Wänden, das sind die Naturwunder, die uns hier erwarten. Nur allzubald hatten wir das Spaltenlabyrinth hinter uns und fuhren auf der darüber gelagerten Terrasse, nunmehr schon angesichts des überwältigenden Nordabfalles des Venedigers, weiter, bis wir an einer geeigneten Stelle den Hang zur Hütte anschneiden konnten; bald nachher begannen wir, uns in diesem so günstig gelegenen, von Schneeschuhfahrern oft aufgesuchten Hochasyl häuslich einzurichten.

Es war mittlerweile Abend geworden, als ich allein vor die Hütte hinaustrat, um noch einen Blick in die winterherrliche Welt vor uns zu werfen. Ein letzter fahler Schein des Tages huschte über die eisigen Häupter, die mich umgaben. Wie flüssiges Silber flutete der breite Gletscherstrom unter mir talab. Kein Lüftchen regte sich, keine trübende Wolke war sichtbar. Über dem edlen Haupt des Venedigers erglänzte der erste Stern, von sanftem Lichte unbeschreiblicher Verklärung übergossen ragte der stolze Bau des Eisriesen in den stahlblauen Azur.--- In den Hängen des Keeskogels waren wir tags darauf zum Zwischensulzbachtörl emporgestiegen, wo uns die ersten Sonnenstrahlen blitzend grüßten, und fuhren nun auf dem Untersulzbachkees der Scharte zwischen Groß- und Kleinvenediger zu. Knapp unter dieser ließen wir unsere Schneeschuhe zurück, da wir in dem steilen Firn ohne sie besser fortzukommen hofften. Wir betraten auf der üblichen Sommerroute das Schlattenkees, überquerten mehrere Spalten und stiegen über den letzten, ziemlich steilen Firnhang vollends zur Spitze auf, von der sich uns die unermeßliche Rundschau in kristallner Klarheit erschloß.

Die Ötztaler Rivalen grüßen herüber, die Nördlichen Kalkalpen von der Zugspitze bis zum Dachstein, die Hörner und Schneedome der Glocknergruppe, die kühnen Türme der Südlichen Kalkalpen in langer Reihe, fern am Horizont Ortler und Bernina, sie alle waren heute in voller Pracht sichtbar und ihr unvergeßliches Bild der Lohn für jene „Mühen", die dem Bergsteiger ja schon an sich hoher Genuß sind. Nach allen Seiten hin wallen die Firnströme hinab in den jungen Frühling, der dort unten so kräftig atmet und in den Wonnen des Lichtes schwelgt. Nur hier auf unserer sonnigen und doch so tief winterlichen Höhe scheint die Zeit stille zu stehen, denn hier herrscht ewiger Winter, das jugendfrische Knospen, das gewaltige Regen des Frühlings dringt nie herauf in diese Region schimmernder Starrheit!

Hochbefriedigt ward endlich Abschied genommen von der hehren Zinne. Vorsichtig stiegen wir über die schon stark erweichten Schneebrücken hinab und gelangten bald zu unseren getreuen Brettern. Mit keinem König hätt' ich getauscht, als ich dann, mit Windeseile dahingleitend im tiefen Pulverschnee, über das Untersulzbachkees hinabfegte. Von den Sorgen der Welt und den Mühen des Lebens mich frei wissend, schwellte Jubelgefühl meine Brust, daß sich ihr ein Juhschrei entrang, der widerhallend mein Stolz- und Siegesbewußtsein den Wänden dieses Hochtals kündete! Das Zwischensulzbachtörl vereinigte uns alle und nun ging's in dem feuchtsalzigen Firn über das Obersulzbachkees hinab. Wieder durchschneiden unsere Schneeschuhspitzen in ungehemmtem Schuß zischend und knisternd den Schnee. Eine ununterbrochene Doppellinie, die Spur unseres vortägigen Hüttenaufstieges, die hier den Gletscher verläßt, wird sichtbar, immer weiter und weiter eilen unsere Gleithölzer in hindernisloser Fahrt, bis wir vor der „Türkischen Zeltstadt" anhalten. Jetzt heißt es gechickt sich durchschlängeln zwischen den lauernden Abgründen und Eiswänden des Bruches. Vorsichtig, an meterbreiten Klüften vorbei, fahren wir hinab. Immer näher rücken die Spalten von beiden Seiten heran, bis sie nur mehr eine schmale Durchfahrt freilassen; was dann folgt, können wir nicht sehen. Langsam und erwartungsvoll versuche ich diesen Ausweg und mit einem Freudenruf künde ich meinen Gefährten, was ich vor mir sehe. Die sanftgeneigte Gletscherzunge habe ich erreicht, und schon sause ich schnurgerade hinab in dem weißen Element, das den Brettern soviel Leben gibt. In zahlreichen Schwüngen und Bögen fahren wir dann vom Ende des Keeses zur Aschamalpe ab und nach einer längeren Rast über den fast ebenen Talboden zur Berndlalpe hin. Hier beginnt die flotte Fahrt von neuem. Durch den Hochwald geht es jetzt hinab der Talöffiiung zu, und solange noch winterliches Weiß vorhanden, wird gefahren. Dann wandern wir, die treuen Bretter geschultert, hochbefriedigt hinaus zur Bahn.